What If Fossil Fuel Companies Paid Us to Stop Using Their Products?

Ray Welch, May 18, 2021

Here’s a way to manage both fossil fuel lobbying power and the economic impact of a rapid reduction in fossil fuel use: get the fossil fuel companies to PAY individuals to stop using their products.

That’s in essence what a national, annually escalating fee-and-dividend program would do, as proposed in HR 2307, the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act. Under fee-and-dividend, the fossil fuel companies pay the fee on the carbon content of the resource when it comes out of the ground, and 100% of the revenue goes to individuals in equal shares.

For most people, the amount of the dividend would exceed the cost increases in goods and services caused to the extent that the fossil fuel companies pass the fee onto their customers. Meanwhile, businesses would squeeze carbon out of their supply chains to keep their prices economically competitive.

Fee-and-dividend could be implemented right away. The fossil fuel companies already report and remit taxes to the Federal government based on the energy content of oil, gas, and coal, and the Dept of Treasury already issues monthly checks to individuals by the millions (e.g., Social Security).

Fee-and-dividend wouldn’t preclude any measure in the House Select Committee’s report on the climate crisis, as this analysis sponsored by Business Climate Leaders shows. It’s a stand-alone action that would jump-start immediate reductions in carbon dioxide (“carbon”) emissions, while leaving the field open for additional measures. Many of the measures in the House report would be easier to implement if a known and reliable carbon price trajectory were in place.

Fee-and-dividend would create that trajectory. The annually-increasing dividend would make this carbon-emissions-reducing system as politically popular and durable as Social Security.

The Fee Would Shift the Strategic Approach of Fossil Fuel Companies

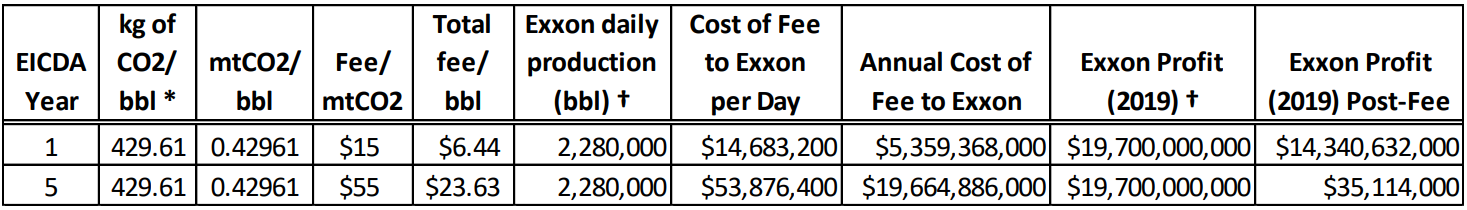

The example below uses Exxon to illustrate how all fossil fuel companies would be motivated to follow BP in an orderly, planned transition from the fossil fuel business. If fee-and-dividend had been in place in 2019, the fee for Exxon would have been substantial: $5.4 billion, which was 27% of profits. Assuming all else equal, in Year 5, the fee would grow to 99.8% of 2019 profits.

Of course, this example is highly simplified to illustrate the scale of the fee, and doesn’t account for the complex dynamics that would ensue if fee-and-dividend were in place. But it’s easy to see that the scale of the fee would affect strategic thinking in the C-suites of fossil fuel companies everywhere.

If Exxon Had to Pay the Carbon Fee:

* https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gases-equivalencies-calculator-calculations-and-references

* https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gases-equivalencies-calculator-calculations-and-references

† https://www.statista.com/topics/1109/exxonmobil/

2019 is used because ExxonMobil had a net operating loss of $22.5 billion in 2020. If the Year 1 carbon fee had been in effect in 2020, the loss would have been $27.9 billion.

Given the predictable fee increases, fossil fuel companies will forecast a steady decline in profitability. They’ll act accordingly, immediately, in something of a self-fulfilling dynamic, by sharply curtailing new fossil fuel investment and going into maintenance mode for existing investments. This would very likely halt Keystone XL and all other new pipelines.

Exploration and drilling would also contract, to the extent it required any investment that wouldn’t be recovered in just a few years, rather than the usual 20-30 years. New fossil fuel investments simply won’t pencil out.

The Dividend Would Push Businesses and Consumers to Alter Their Purchasing Habits

Because businesses and individuals could be certain that the price of fossil fuels will rise every year, they’d both be very motivated to shift toward clean energy sooner rather than later. That would accelerate the virtuous investment and innovation cycle in the clean energy space. There’d be robust price competition, which would drive down clean energy costs and amplify its rapid deployment. Clean energy growth would mirror, inversely, the rapid decline in fossil fuel usage.

Businesses wouldn’t receive a dividend. But they’d vigorously drive carbon out of their cost structure to remain price-competitive.

For individuals, the dividend would be modest in Year 1, somewhere between $25 to $50/month. But by Year 10, a 2013 study shows that it would reach $396/month for a family of four, even though overall fossil fuel usage declines substantially. (For the pool of money available for the dividend, the decline in usage is offset by the annual increase in the fee.) $396/month is meaningful for a family in the lowest two income quintiles, making $3,100/month or less. The bottom three quintiles, at the least, would be financially neutral or better off under fee-and-dividend. A 2017 study by the Department of Treasury pegs the break-even at 70% of the population.

What will we do when fossil fuels are reduced to the point that the pool of money from the fee no longer supports a meaningful dividend? Given that the fee increases by $10 or $15 every year, that day is a ways off. The dividend is meant to help everyone cope with the rise in fossil fuel prices. It isn’t designed to be a permanent Universal Basic Income. But it could serve as a transitional model for a deliberately structured UBI, if policy-makers want to go that route.

Fee and Dividend: A No-Regrets First Step

Is fee-and-dividend a silver bullet? No. But the alternative is to continue to let the fossil fuel companies to pollute for free, and to transfer the environmental and health costs to us individuals. We live in a world where money is real. Trying to work around that reality by relying solely on regulations and standards, and not applying a socially just carbon fee, would take enormous resources, meet enormous resistance, and require years to ramp up to the required scale. All praise to California’s decades of green energy mandates and carbon regulation, but the state’s total annual GHG emissions in 2018 (latest available) were only 10% lower than they were in 2000 (1). That’s just not good enough.

The money has to shift from the side of fossil fuel pollution to the side of emissions reductions. We got into the climate mess largely through normal economic activity, and it’s a big part of how we have to get out of it. Fee-and-dividend is a no-regrets first step.

——————————–

(1) p.2, California Greenhouse Gas Emissions for 2000 to 2018: Trends of Emissions and Other Indicators, California Air Resources Board.